Ventilation Weaning, Extubation and Decannulation

Some research shows that around two-thirds of mechanically ventilated patients can be weaned in ICU after SCI (Schreiber et al. 2021). Liberation from ventilator support is a primary goal for patients with SCI, but the ability to wean off the ventilator is primarily determined by the level of injury. A C1 or C2 level injury may result in lifetime ventilator dependency because there is loss of function of the phrenic nerves that control the diaphragm. A C3-C4 injury is more variable in whether independent breathing will be achieved, with approximately 40% or more of these patients are successfully weaned (Berney et al. 2011). Patients with an injury at C5 or lower often need ventilation only in the earliest stages of the injury and during spine fixation surgery but are able to wean from the ventilator soon after. The recent systematic review of Schreiber et al. (2021) included 39 studies (with a total number of 14,637 patients, which 13,763 were in ICU) and found that, apart from a high-level lesions, other conditions which appear to be associated with increased odds of weaning failure were a high number of comorbidities, high Injury Severity Score, elevated heart rate, and presence of tracheostomy. Furthermore, shorter time to admission to a specialized SCI center, high-level lesions (C1-C4 vs C5-C8), complete lesion, low tidal volume and high positive end-expiratory pressure within 24 hours from admission, and presence of tracheostomy were associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation (Schreiber et al. 2021). Although the present review focuses on ventilator weaning, extubation, and decannulation during the first weeks and months of SCI, this process can span much longer in some cases (Galeiras Vázquez et al. 2013). For more information on long-term ventilator weaning, refer to the section “Mechanical Ventilation and Weaning Protocols” in the Respiratory Management chapter in SCIRE.

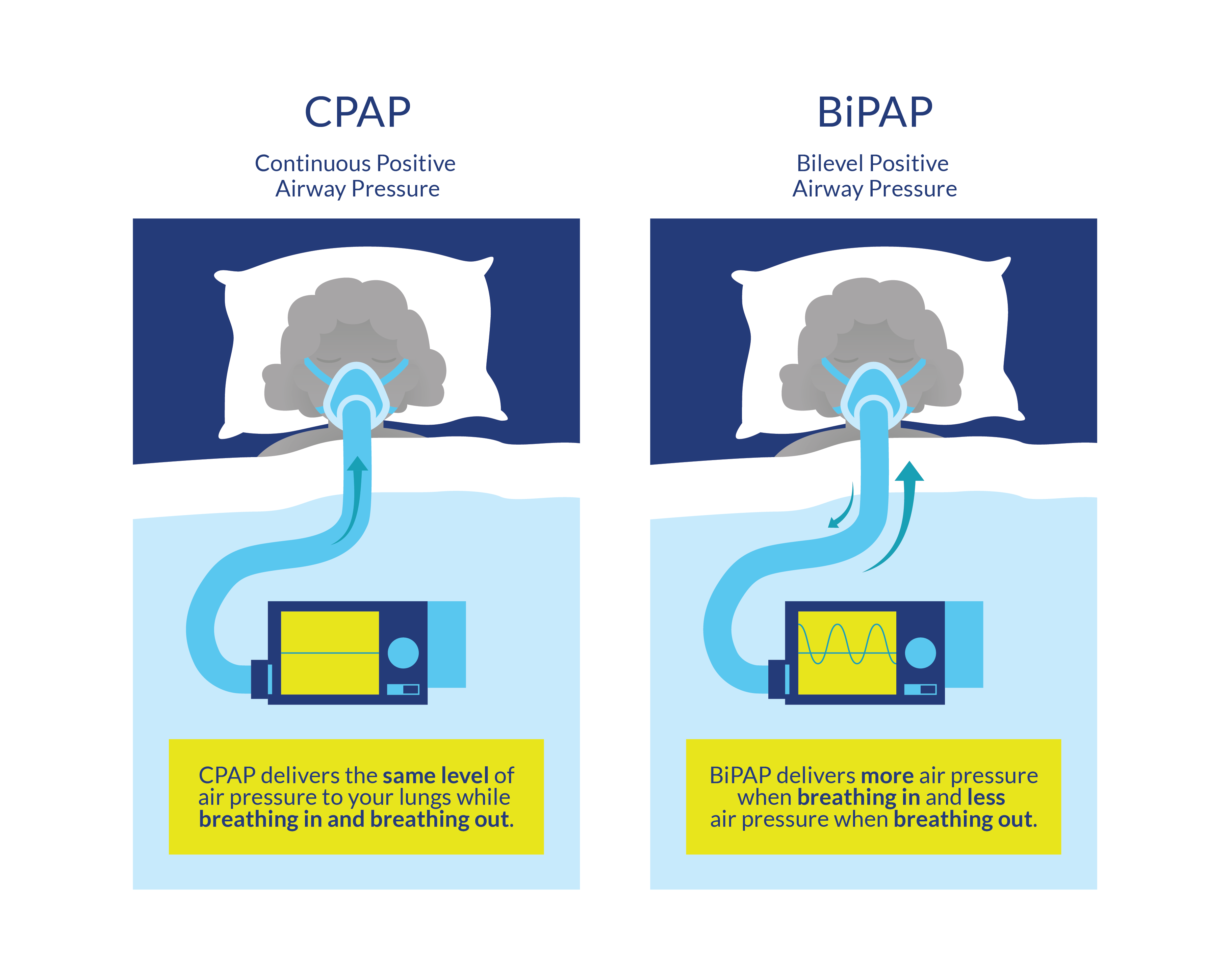

Before a patient initiates the weaning process, extubation or decannulation, a vital capacity of 1500 mL, clear lung radiographs, stable blood gases, stable heart rate and respiratory rate, and stable excretion levels must be achieved (Chiodo et al. 2008; Peterson et al. 1999). To begin weaning, a patient is removed from the ventilator for short periods of time that progress to longer and more frequent intervals of independent breathing. There are several protocols for this process; progressive ventilator-free breathing (PVFB), intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV), and pressure support are the most common protocols (Weinberger & Weiss 1995). Newer studies are also examining the safety of higher tidal volumes for ventilator weaning (Fenton et al. 2016). PVFB is the process whereby a patient experiences intervals of ventilator-free time that increases in length throughout the day to build muscle tone (Galeiras Vázquez et al. 2013). If PVFB is the chosen method for weaning, a patient can be weaned using either low tidal volume or high tidal volume. Using larger ventilator volumes (greater than 20 mL/kg) is thought to be more effective than low tidal volume and can resolve atelectasis and increase surfactant production; however, this method is also associated with more pulmonary complications in certain patient cohorts (Peterson et al. 1999; Wallbom et al. 2005). IMV is the process whereby the ventilator provides a predetermined number of breaths within a certain time frame and the patient is encouraged to spontaneously breathe in between them when they can. The number of breaths decreases as patients gain pulmonary independence. Lastly, pressure support ventilation is the technique whereby the patient must initiate every breath and the ventilator assists with the rest of the breathing process. Biphasic positive airway pressure (BiPAP) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) are two systems designed for non-invasive respiratory pressure support (Tromans et al. 1998). In addition to these ventilation procedures, transition from intubation to a tracheostomy, immediate extubation, and the use of diaphragmatic pacemakers are alternatives to patients requiring full time ventilation.

Figure 2. Description of the BiPAP and CPAP systems, designed for non-invasive respiratory pressure support

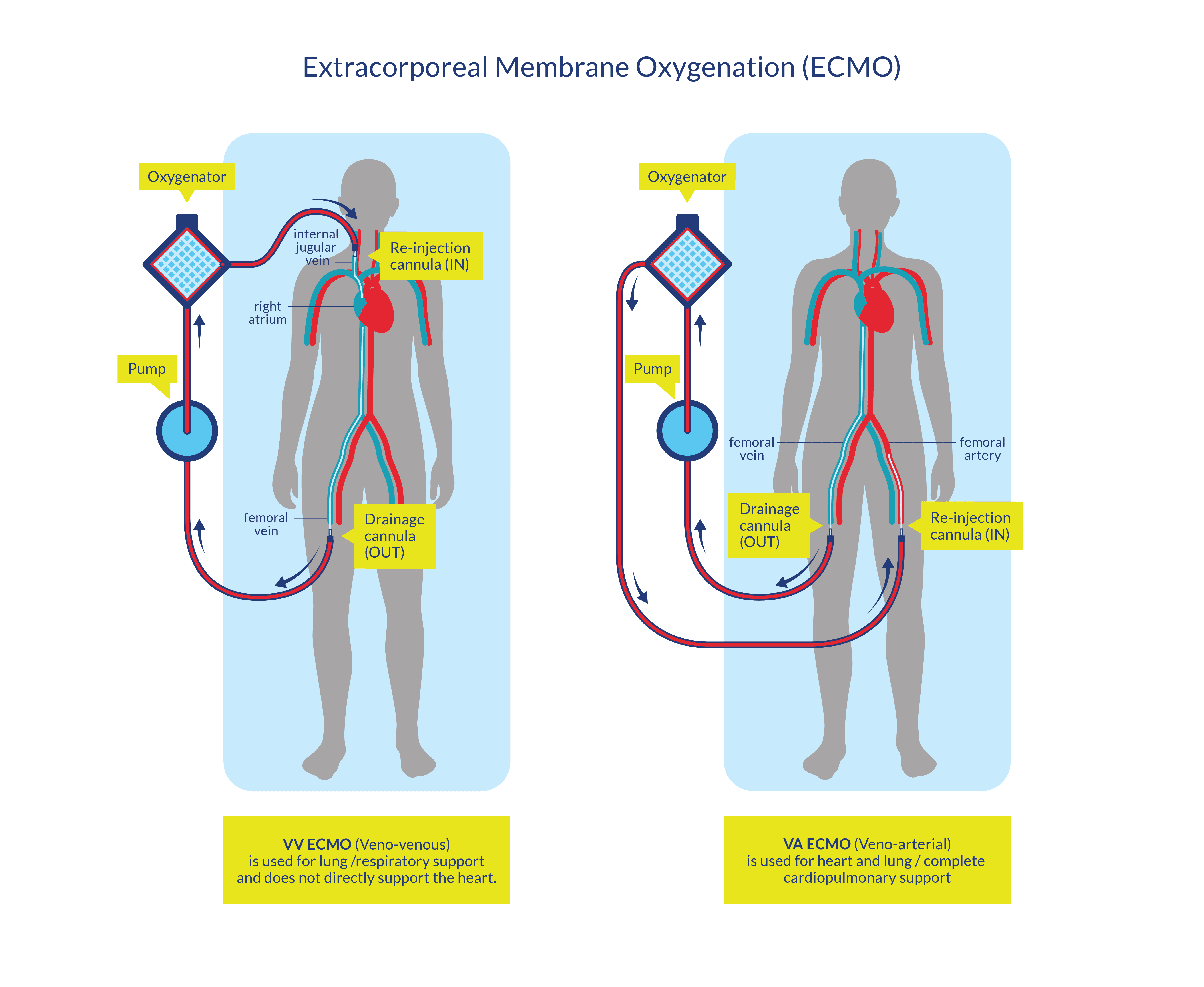

In very rare cases if lung-protective ventilation cannot be conducted, extracorporeal lung support (iLA/ECMO) can provide systemic tissue oxygenation and decarboxylation while avoiding ventilator-associated barotrauma to the lung tissue (Lotzien et al. 2017). Moreover, venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can be used as a salvage therapy for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and refractory hypoxia (Tsai et al. 2015). Venovenous ECMO primarily provides gas exchange to replace or support lung function (Lotzien et al. 2017). Blood is drained from the inferior vena cava via a femoral venous cannula or from the superior vena cava via an internal jugular venous cannula (Lotzien et al. 2017). The blood is pumped via the oxygenator back into the venous system through the internal jugular vein or through the second femoral venous cannula (Lotzien et al. 2017). Alternatively, a dual-lumen cannula can be employed for simultaneous venous drainage and return (Lotzien et al. 2017). Venovenous ECMO can provide partial to full extracorporeal pulmonary support with blood flow up to 6 L/min (Lotzien et al. 2017). On the other hand, pumpless systems, which use the arteriovenous pressure gradient of the patient to create a shunt from the artery to the vein (interventional lung assist (iLA); facilitate extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal and can support mechanical ventilation by enabling a low tidal volume and a reduced inspiratory plateau pressure (Zimmermann et al. 2009).

Figure 3. Characteristics of the veno-venous and veno-arterial ECMOs procedures

Decannulation, or removal of the tracheostomy, of patients with SCI is a critical milestone in their recuperation (Sun et al. 2022), but evidence for the decannulation of people with SCI is lacking. People may not meet the traditional criteria for decannulation and should be assessed on an individualized basis (Ross & White 2003; Bach & Alba 1990).

Discussion

In comparing methods of ventilator weaning, one case control showed that PVFB allowed patients to wean faster than IMV (Peterson et al. 1994). This finding is recommended by the Paralyzed Veterans of America Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine (2005) and is consistent with other studies that examined non-SCI patients (Brochard et al. 1994; Esteban et al. 1995). The only study to investigate the efficacy of high versus low tidal volume on ventilator weaning found that high tidal volume resulted in faster weaning and more instances of resolved atelectasis than low tidal volume (Peterson et al. 1999). The weaning period for patients on high tidal volume ventilation was an average of three weeks sooner than those who received low tidal volume ventilation.

Kim et al. (2017) retrospectively studied 62 patients with complete or sensory incomplete cervical SCI who received an invasive acute phase respiratory management (including mechanically assisted coughing and non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV)) for patients with tracheostomy (n = 60) and endotracheal intubation (n = 2), showing that tracheostomy decannulation was possible and non-invasive respiratory intervention, including NIV and mechanically assisted coughing, was an effective long-term alternative to tracheostomy.

Ross and White (2003) described a case series of four people with SCI who were successfully decannulated despite the presence of traditional contraindications such as evidence of aspiration. These four people were carefully selected by a multidisciplinary team who opted for decannulation after assessing the overall risks of decannulation versus the risks of prolonged tracheostomy. Further studies examining and refining the criteria for decannulation of people with SCI are necessary.

Successful decannulation and extubation has been found to be affected by the level and severity of injury whereby a higher rate of extubation is more likely to be achieved in patients with lower spinal cord injuries (Call et al. 2011). Decannulation is performed with a higher rate of success among patients with lower-level cervical injuries compared to those with higher cervical cord injuries (Nakashima et al. 2013). The presence of a tracheostomy was found by Kornblith et al. (2014) to reduce attempts at extubation, but in cases where extubation was successful on the first attempt, patients had shorter intensive care unit and hospital stays compared to those who have failed one or more times (Call et al. 2011). Kornblith et al. (2014) also noted that among the patients included in their study, the majority of persons did not require mechanical ventilation at the time of discharge indicating that the many patients with SCI can be successfully weaned from ventilators; however, this was significantly more common in patients who did not have a tracheostomy compared to those who did require this procedure (p < 0.05).

Lotzien et al. (2017) described the first case series of seven patients with SCI and post-traumatic lung failure treated with lung support with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or interventional lung assist (iLA) devices and showed that this therapy was feasible and a life-saving procedure (71.4%).

Conclusion

There is level 3 evidence (from one case control study: Kornblith et al. 2014) that patients with acute SCI who do not require tracheostomies have a higher success rate of mechanical ventilation weaning compared to those who do require this procedure.

There is level 3 evidence (from two case control studies: Nakashima et al. 2013; Call et al. 2011) that higher level SCI correlates with lower rates of decannulation and extubation in patients with acute SCI.

There is level 4 evidence (from one case series study: Kim et al. 2017) that an invasive acute phase respiratory management (including mechanically assisted coughing and NIV) for patients with cervical SCI receiving tracheostomy or endotracheal intubation provides successful in tracheostomy decannulation; and noninvasive respiratory intervention, including NIV and mechanically assisted coughing, is an effective long-term alternative to tracheostomy.

There is level 4 evidence (from one case series study: Ross & White 2003) that decannulation can be successful in people with evidence of aspiration.

There is level 2 evidence (from one cohort study: Peterson et al. 1999) that higher ventilator tidal volumes may speed up the mechanical ventilation weaning process compared to lower ventilator tidal volumes in patients with acute SCI.

There is level 3 evidence (from one case control: Peterson et al. 1994) that progressive ventilator-free breathing is a more successful method of weaning patients with acute cervical SCI from mechanical ventilation than intermittent mandatory ventilation.

There is level 4 evidence (from one case series: Lotzien et al. 2017) that extracorporeal lung support is a feasible therapy with a high survival rate for patients with SCI and post-traumatic lung failure.