Primary Care and Cardiovascular Health

People with SCI have a 2x higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than the general population. Lifetime prevalence for CVD in people with SCI is estimated at 30-50%, but may actually be as high as 60-70%, given asymptomatic cases, and it is now the leading cause of death for people with SCI. Here’s why:

- People with SCI have a greater prevalence of obesity than general population. Denervated muscles, loss of muscle mass, lower levels of physical activity, and limited access to physical activities in people with SCI all results in more obesity.

- People with SCI have lower energy expenditure, and thus lower energy/food requirements. Lower levels of physical activity, no movement in lower limbs, and a lower thermic effect of food result in decreased energy expenditure and energy needs, but many people with SCI do not decrease how much they eat.

- People with SCI are more likely to have higher central adiposity. Due to limited activity, loss of muscle mass, and lack of core muscle control, people with SCI are also 58% more likely to have more fat accumulation around their middle.

- People with SCI also tend to have impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Due to altered sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system functioning, people with SCI have also been shown to have higher rates of diabetes and lower levels of HDL-C.

- Acute cardiac events can be harder to detect in people with SCI because of impaired sensation and atypical presentation (chest pain may not occur, or if it does people with SCI might not feel it, but instead you may see spasticity, fainting, or shortness of breath).

Proactive treatment of risk factors for cardiovascular disease is essential for your patients with SCI.

Pay special attention to:

- Nutrition: Obesity has been estimated at 50-75% in the SCI population, and significant nutritional inadequacies are common. First Line Treatment – The Clinical Practice Guidelines in Nutrition for People with SCI’s recommends that nutritional assessment be done for the prevention and treatment of obesity in people with SCI. The good ‘rules of thumb’ are to: encourage a ‘heart-healthy diet’ with <5% saturated fat, <2400 mg sodium, and a caloric reduction of 10-15% in people with tetraplegia, and of 5-10% in people with paraplegia (from pre-injury diet). Second line treatment: consider referral to a dietician/nutritionist, preferably with experience with SCI or other lower activity population, to ensure recommendations take into consideration SCI-specifics and norms for weight and body composition, and adjust energy level or implement weight management strategies as appropriate.

- Pharmacological management: Guidelines for high-risk patients apply to people with SCI for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, but pharmacological management of obesity is contraindicated. SCI-specific recommendations have not yet been established for blood cholesterol or diabetes, so recommendations for higher-risk patients without SCI should be applied (e.g., Multisociety Guidelines on Management of Blood Cholesterol). For example, adults aged 40 or older with LDL greater than 70 mg/dL ought to be offered moderate intensity statins, and those with greater than 190 mg/dL higher intensity statins; barring major lifestyle changes, statin therapy must usually be continued for life. For diabetes or pre-diabetes management, HbA1c value of 5.7% or greater is diagnostic of pre-diabetes and 6.5% is indicative of frank diabetes -Metformin is the preferred first-line agent for treating someone with an HbA1c value of greater than 7%.

- Lifestyle management: Evidence-based guidelines recommend 150 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity, as well as strength training for major muscle groups. Popular modes of exercise include arm ergometry, wheelchair propulsion, wheelchair sports, swimming, circuit training and electrically stimulated cycling. Prior to participation in physical activity, patients should be made aware of the potential for overuse injuries, autonomic dysreflexia, thermal dysregulation, and increased pressure sore risk.

• Smoking cessation is also a key part of effective lifestyle management. Evidence has shown that lifestyle changes are significantly more likely to be sustained if monitored by a physician. - Blood Pressure must be considered for overall health as well as for exercise prescription.

Blood pressure (BP) is commonly lower in people with SCI, particularly those with lesions above T7 (e.g., 100/60 mm Hg). However, they are prone to BP drops and spikes due to autonomic instability/interference and postural influences.

° Establish your patient’s baseline BP values when standing, sitting, and lying down. Measure blood pressure at every routine visit and/or at least annually to monitor any changes.

° Apply evidence-based guidelines for treating hypertension as per general population; for most, the threshold for initiating pharmacotherapy is >140/90 mm Hg. Patient characteristics and current medications must be considered when selecting an antihypertensive agent (e.g., diuretics and bladder management). - Reduce the number of cardiometabolic risk factors to <3 if possible, including:

a. Reduce body fat to achieve body mass index (BMI) ≤ 22 kg/m2 or waist circumference to <34 inches

b. Reduce triglycerides to ≤ 150 mg/dL and increase HDL-C to ≥ 40 mg/dL

c. Reduce fasting blood glucose to ≤ 100 mg/dL and/or HbA1c to < 7%

d. Encourage exercise ≥ 150 minutes per week to increase energy expenditure sufficiently to achieve neutral of negative (fat loss) energy balance

e. Encourage adoption of a heart-healthy diet with focus on fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, legumes, and nuts to achieve neutral or negative (fat loss) energy balance

f. Recommend limiting saturated fat to 5% to 6% of total caloric intake

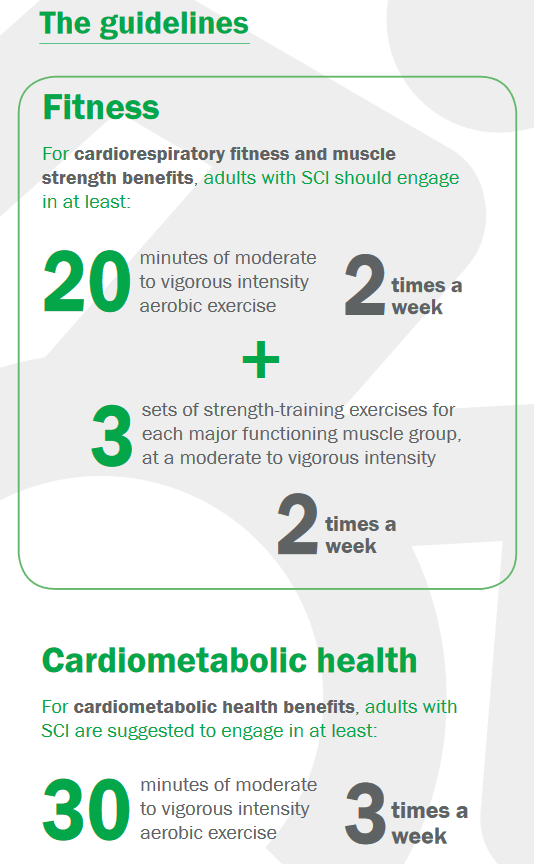

Download Exercise Guidelines for People With SCI

For cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength benefits, adults with SCI should engage in:

- At least 20 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise 2 times per week.

- 3 sets of strength exercises for each major functioning muscle group, at a moderate to vigorous intensity, 2 times per week.

For cardiometabolic health benefits, adults with SCI are suggested to engage in:

- At least 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise 3 times per week.

Proactive screening is important for patients with SCI so that under-diagnosis, lack of sensation, and/or conservative treatment do not contribute to higher number of cardiovascular problems. Screen for all cardiovascular risk factors at least annually.

Risk Factor |

Details |

Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Pressure (BP) | Baseline BP will generally be lower for people with SCI (100/60 mmHg +/- 20).

It is important to establish your patient’s standing, sitting, and lying (supine) BP to establish their baseline and to properly monitor fluctuations. |

Each regular health care visit or at least annually |

| Waist Circumference and/or Body Mass Index (BMI) | Waist circumference may be more accurate for assessing health, fitness, and adipose tissue in people with SCI. Ideal = less than 34 inches.

BMI ideal for people with SCI is lower than general population = 22 or less kg/m2. |

Waist Circumference and/or BMI should be measured at least annually.

Smoking, Physical Activity, and Diet should be discussed each regular health care visit. |

| Triglycerides | If your patient regularly eats more calories than they burn, they may have high triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia)

Normal: Less than 150 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), or less than 1.7 millimoles per liter (mmol/L) |

A minimum of every 1 to 2 years for males age 45 and older, females age 55 and older (SCI = High Risk for CVD patient).

Note: Fasting prior to blood test is required for an accurate reading. |

| Blood Glucose Test and/or A1C test | To diagnose diabetes or prediabetes, the percentages commonly used are:

Normal: A1C below 5.7% |

The American Diabetes Association recommends testing for prediabetes/risk for future diabetes for all people beginning at age 45 years. If tests are normal, it is reasonable to repeat testing at a minimum of 3-year intervals.

People with SCI should be tested more regularly if they have physical symptoms of blood sugar dysregulation (e.g., dizziness, fatigue, obesity) or if they are physically active less than 3 times per week. |

| Total Cholesterol, including low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) | Fasting lipid profile or at minimum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides should be assessed annually, with diet, exercise, and statin or extended-release niacin prescribed to achieve target triglycerides ≤150 mg/dL and HDL-C ≥40 mg/dL. | Guidelines for adults without SCI is every 4-6 years; therefore screening should be more often for your patients with SCI (accordingly) based on patient’s age and number of risk factors for CVD. |

Sources: Heart-Health Screenings – American Heart Association, Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) Test, Triglycerides test

A referral to a cardiologist should be considered in all patients with 3 or more risk factors for cardiovascular disease (who you have not been able to move to <3 risk factors despite a period of treatment time/surveillance)

- If waist circumference is greater than 34 inches, or if body mass index (BMI) greater than 22 kg/m2

- If triglycerides are greater than 150 mg/dL or HDL-C is less than 40 mg/dL

- If fasting blood glucose is greater than 100 mg/dL and/or HbA1c is greater than 7%

- If person exercises less than 150 minutes per week (moderate to vigorous)

- If diet is not primarily comprised of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, legumes, and nuts, and saturated fats makes up more than 6% of total caloric intake.

Consider referral to a dietician/nutritionist, preferably with experience with SCI or other lower activity population, to ensure recommendations take into consideration SCI-specifics and norms for weight and body composition, and adjust energy level or implement weight management strategies as appropriate.

Consider referral to an exercise specialist with experience working with people with SCI or neurological disabilities. Patients should also consult with a health professional who is knowledgeable in the types and amounts of exercise appropriate for people with SCI. Individuals with a cervical or high thoracic injury should be aware of the signs and symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia during exercise.

Sources: Stillman et al. 2020 A Provider’s Guide to Vascular Disease, Dyslipidemia, and Glycemic Dysregulation in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2020;26(3):203-208. SCI Nutrition Guidelines (2009), SCI Exercise Guidelines in English.

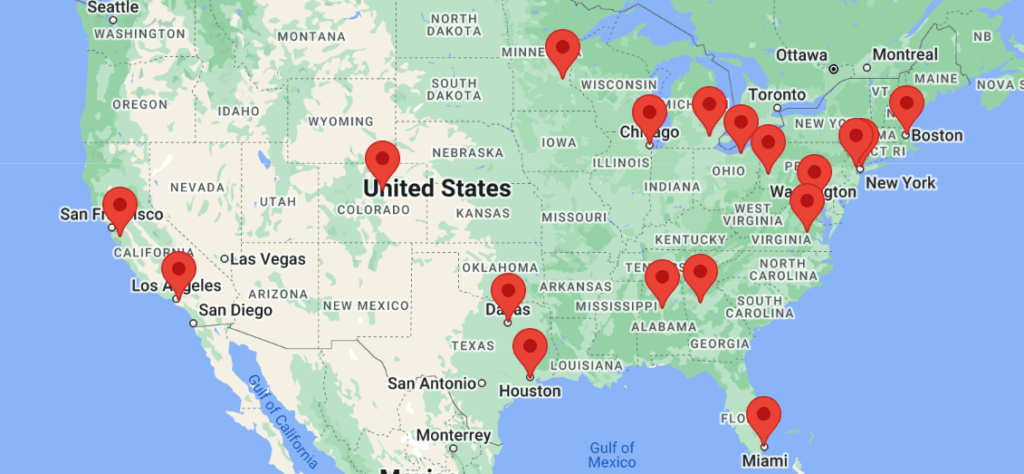

Access to specialists (cardiology, physiatry) may be limited, particularly if you do not live in or near a major city.

Advanced screening re your patient’s cardiovascular functioning, health, and fitness may best be handled by a cardiologist, physiatrist, or exercise specialist with experience in SCI. These specialists will be essential for your patient’s health care team.

If you or your patients with SCI are not already connected, please try to gain access to a urologist or physiatrist near you. Refer to the list of SCI centers worldwide below:

- Australia (Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service): https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qscis

- Canada: https://praxisinstitute.org/research-care/key-initiatives/national-sci-registry/registry-sites

- Europe (enrolled in European Multicenter Spinal Cord Injury Study): https://www.emsci.org/index.php/members

- UK: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/BSF_List-of-Neurocentres-in-the-UK.pdf

- USA: https://www.spinalcord.com/spinal-cord-injury-hospitals-rehabilitation-directory

(Please email SCIRE Professional if we do not have a list for your country)

Additional Resources:

Infoline at SCI-BC has peers (people with SCI) that are trained in Exercise Coaching for people with SCI. Contact via email (info@sci-bc.ca) or call the InfoLine at 1-800-689-2477 (Open M-F 9am-5pm PST).

ProActive SCI Intervention Toolkit: A step-by-step resource designed to help physiotherapists work with their clients with SCI to be physically active outside of the clinic. Found on SCI Action Canada website.

Exercise Guidelines for People With SCI (in multiple languages)

- Stillman M, Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Goldberg R, Gater DR. A provider’s guide to vascular disease, dyslipidemia, and glycemic dysregulation in chronic spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2020; 26(3): 203-208.

- Gill S, Sumrel RM, Sima A, Cifu DX, Gorgey AS. Waist circumference cutoff identifying risks of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease in men with spinal cord injury. PLoS One 15(7): e0236752.

- Bauman WA, Spungen AM. Coronary heart disease in individuals with spinal cord injury: Assessment of risk factors. Spinal Cord 2008; 46(7): 466-76.

- Yarar-Fisher C, Heyn P, Zanca JM, Charlifue S, Hsieh J. & Brienza DM. Early identification of cardiovascular diseases in people with spinal cord injury: Key information for primary care providers. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2016;98(6), 1277-1279. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2016.10.001

- Actionable Nuggets 4th edition (2019). Screening for cardiovascular risk in SCI. https://actionnuggets.ca/2-screening-for-cardiovascular-risk-in-sci/. Accessed on March 13, 2023.

- Actionable Nuggets 4th edition (2019). Management of cardiovascular risk in patients with SCI. https://actionnuggets.ca/3-management-of-cardiovascular-risk-in-patients-with-sci/. Accessed on March 13, 2023.

- Nash MS, Groah SL, Gater Jr DR, Dyson-Hudson TA, Lieberman JA, Myers J, … & Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. (2018). Identification and Management of Cardiometabolic Risk after Spinal Cord Injury: Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Providers. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 24(4), 379-423.

- Sumrell RM, Nightingale TE, McCauley LS, Gorgey AS. Anthoropometric cutoffs and associations with visceral adiposity and metabolic biomarkers after spinal cord injury. PLoS One 2018; 13(8).

- Gorgey AS, Gater DR Jr. Prevalence of obesity after spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2007;12(4):1-7.

- Gater DR, Farkas GJ. Alterations in body composition after SCI and the mitigating role of exercise. In: Taylor JA, ed. The Physiology of Exercise in Spinal Cord Injury. Springer; 2016: 175-198.

- Farkas GJ, Gater DR. Neurogenic obesity and systemic inflammation following spinal cord injury: A review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41(4):378-387.

- Gater DR Jr, Farkas GJ, Berg AS, Castillo C. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in veterans with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42(1):86-93.

- Lee CS, Lu YH, Lee ST, Lin CC, Ding HJ. Evaluating the prevalence of silent coronary artery disease in asymptomatic patients with spinal cord injury. Int Heart J. 2006;47(3):325-330.

- Laughton GE, Buchholz AC. Lowering body mass index cutoffs better identifies obese persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009; 47(10): 757-62.

- Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen SA, et al. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 200543(7):408-416.

- Spungen AM, Adkins RH, Stewart CA, Wang J, Pierson RN, Waters RL, et al. Factors influencing body composition in persons with spinal cord injury: A cross-sectional study. J.Appl Physiol 2003; 95(6): 2398-407.

- Stillman MD, Aston CE, Rabadi MH. Mortality benefit of statin use in traumatic spinal cord injury: A retrospective analysis. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(4):298-302.

- Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SBB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: A consensus statement from shaping America’s health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Obesity 2007; 15(5): 1061-7.

- Groah SL, Nash MS, Ward EA, et al. Cardiometabolic risk in community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31(2):73-80.

- Libin A, Tinsley EA, Nash MS, et al. Cardiometabolic risk clustering in spinal cord injury: Results of exploratory factor analysis. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2013;19(3):183-194.

- Nash MS, Mendez AJ. A guideline-driven assessment of need for cardiovascular disease risk intervention in persons with chronic paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(6):751-757.

- Toth PP, Potter D, Ming EE. Prevalence of lipid abnormalities in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003- 2006. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(4):325-330.

- Nash MS, Lewis JE, Dyson-Hudson TA, et al. Safety, tolerance, and efficacy of extended-release niacin monotherapy for treating dyslipidemia risks in persons with chronic tetraplegia: A randomized multicenter controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(3):399-410.

- Duckworth WC, Solomon SS, Jallepalli P, Heckemeyer C, Finnern J, Powers A. Glucose intolerance due to insulin resistance in patients with spinal cord injuries. Diabetes. 1980;29(11):906-910.

- Ravensbergen HJC, Lear SA, Claydon VE. Waist circumference is the best index for obesity-related cardiovascular disease risk in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2014; 31(3): 292-300.

- Tune JD, Goodwill AG, Sassoon DJ, Mather KJ. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl Res. 2017;183:57-70.

- Elder CP, Apple DF, Bickel CS, Meyer RA, Dudley GA. Intramuscular fat and glucose tolerance after spinal cord injury–a cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 2004;42(12):711-716.

- Biering-Sorensen F, Biering-Sorensen T, Liu N, Malmqvist L, Wecht JM, Krassioukov A. Alterations in cardiac autonomic control in spinal cord injury. Auton Neurosci. 2018;209:4-18.

- West CR, Mills P, & Krassioukov AV. Influence of the neurological level of spinal cord injury on cardiovascular outcomes in humans: a meta-analysis. Spinal Cord, 2012;50(7), 484–492. http://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.17

- Cragg JJ, Stone JA, & Krassioukov AV. Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Individuals with Chronic Spinal Cord Injury: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2012;29(11), 1999–2012. http://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2012.2313.

- Martin Ginis KA et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: an update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord 2018; 56: 308-321.

- Gorgey AS, Mather KJ, Gater DR. Central adiposity associations to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in individuals with complete motor spinal cord injury. Metabolism 2011; 60(6); 843-51.

- Farkas GJ, Pitot MA, Gater Jr. DR. A systematic review of the accuracy of estimated and measured resting metabolic rate in chronic spinal cord injury. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metabol. 2019;29(5):548-558.

- Farkas GJ, Pitot MA, Berg AS, Gater DR. Nutritional status in chronic spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(1):3-17.

- Finnie AK, Buchholz AC, Martin Ginis KA, SHAPE SCI Research Group. Current coronary heart disease risk assessment tools may underestimate risk in community-dwelling persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(9):608-615.

For Clinical Practice Guideline recommendations based on your patient’s level of injury and specific complaint, click here for the CAN-SCIP Coach App.

For more information see our Cardiovascular Health and Physical Activity: Cardiovascular Health and Fitness Modules.

Disclaimer

All content and information on this website is for informational and educational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and does not establish any kind of patient-client relationship by your use of this website. The information here has been curated by experts in spinal cord injury treatment but it is not a substitute for actual medical consultation. Always see a medical professional directly for specific treatment for your particular needs including any professional, health-related, legal, medical, or financial decisions.