Risk for Cardiovascular Disease

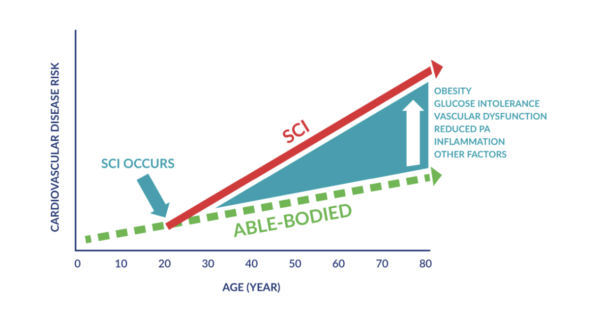

The role of arteriosclerosis (i.e., narrowing and hardening of the arteries) on the development of CVD is clear (Grey et al. 2003). Specifically, people with SCI are at a greater risk of developing arteriosclerosis and thus CVD (shown in Table 2). Persons with SCI appear to be particularly susceptible to the development of arteriosclerosis (Bravo et al. 2004).

A healthy endothelium (the interior lining of blood vessels) is essential for the protection against arteriosclerosis (Anderson 2003). Increasing evidence has examined the vascular health of persons with SCI (de Groot et al. 2005; Zbogar et al. 2008; Phillips et al. 2011), and the effects of exercise training on vascular health in SCI (see recent systematic review of Phillips et al. 2011). However, the volume and level of evidence is quite limited in comparison to what is known about vascular health in the general population and other chronic conditions (such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes) (Phillips et al. 2011). The majority (if not all) of the risk factors for CVD in persons with SCI will have a significant negative impact upon vascular health and function. As such, it is likely that vascular dysfunction is a central step in the development of CVD in persons with SCI.

Various authors have demonstrated reduced peripheral vascular function and/or arterial compliance in SCI (Table 1); however, others have highlighted that when appropriate controls are applied certain markers of endothelial function (e.g., endothelium-dependent and -independent vasodilatation of the superficial femoral artery) may not be appreciably different from the general population (de Groot et al. 2004, Thijssen et al. 2008).

Table 2. Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease in Persons With SCI

| Risk Factor | Literature Support |

|---|---|

| Abnormal lipoprotein profiles | (Brenes et al. 1986; Dearwater et al. 1986; Bauman et al. 1992b; Krum et al. 1992; Maki et al. 1995; Dallmeijer et al. 1997; Bauman et al. 1998; Bauman et al. 1999a; Bauman et al. 1999b) |

| Abnormal glucose homeostasis | (Myllynen et al. 1987; Bauman & Spungen 2001) |

| Increased relative adiposity, elevated body fat and/or reduced lean body mass | (Bauman et al. 1999c; Spungen et al. 2003) |

| Reduced peripheral vascular function and/or arterial compliance | (Wecht et al. 2000; Hopman et al. 2002; Wecht et al. 2003; de Groot et al. 2005; Zbogar et al. 2008; Wong et al. 2012; Phillips et al. 2012) |

| Increased risk for deep vein thrombosis | (Miranda & Hassouna 2000) |

| Abnormal haemostatic and inflammatory markers | (Vaidyanathan et al. 1998; Kahn 1999; Roussi et al. 1999; Kahn et al. 2001; Frost et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2005b) |

| Excessive homocysteine (an amino acid) | (Bauman et al. 2001) |

| Depressed endogenous anabolic hormone levels (e.g. serum testosterone and growth hormone) | (Claus-Walker & Halstead 1982b; Bauman & Spungen 2000) |

| Increased activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (a hormone system that regulates blood-pressure and fluid balance). | (Claus-Walker & Halstead 1982a) |

| Hypertension | (Lee et al. 2005a) |

| Reduced aerobic fitness | (Hoffman 1986) |