Primary Care and Autonomic Dysreflexia

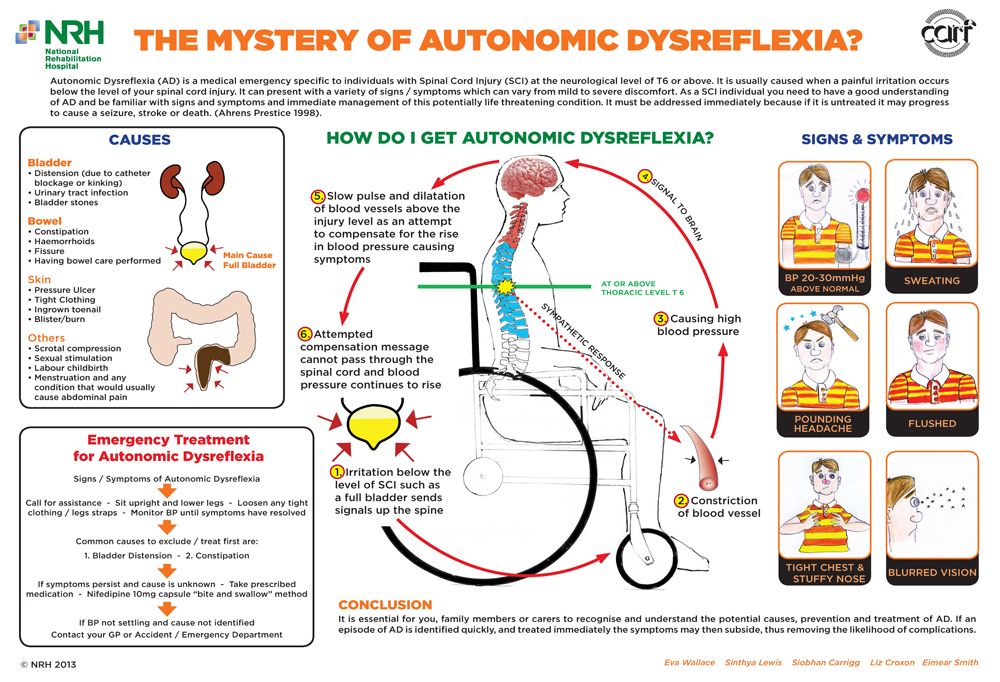

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is a condition that is largely unique to people with SCI (usually those with injuries at T6 or above). It is dangerous spike in blood pressure (20-40 mm Hg above baseline) causing discomfort and more serious medical complications. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Pounding headache

- Skin redness or flushing

- Sweating, usually above level of injury and/or cold and clammy skin, usually below the level of injury

- Blurred vision

- Goose bumps

- Nasal congestion

Episodes may occur as many as 20 times a day. The vast majority of episodes are caused by bladder distension or bowel impaction, but have also been found to be caused by skin irritation, sexual activity, or other systemic issues. Urgent attention is required at the onset of an AD episode, as the consequences can be as severe as stroke or even death.

Ask your patient (and their caregiver if they have one) about autonomic dysreflexia (AD). Most patients with SCI above T6 will have had AD before and be knowledgeable about it, so ask them what usually causes an episode and what is the usual remedy.

An acute episode of AD is a medical emergency. If your patient presents with AD, do the following:

- Place your patient in an upright position.

- Loosen clothing and other restrictions.

- Monitor pulse and BP every 2-5 minutes during the episode.

- Search for and eliminate the precipitating stimulus (i.e., most commonly bladder needs to be emptied or bowel is impacted).

- If neither the bladder or bowel seems to be the cause, perform a complete physical examination looking for pressure spots or ulcers, ingrown nails, or any other potential source of discomfort.

- If these measures do not resolve the AD episode and if the systolic blood pressure remains elevated above 150 mm Hg, consider pharmacological management using topical (e.g., nitroglycerin paste) or oral antihypertensive agents (e.g., rapid-onset, short duration such as nifedipine capsules 5 or 10 mg or captopril 12.5 or 25 mg with the instructions to ‘bite and swallow”). Topical agents are preferred as they can be easily wiped off once the triggering stimulus is resolved and BP returns to normal levels.

- Continue to monitor BP for at least 2 hours after symptoms resolve and consider hospital admission if symptoms persist.

Although the use of fast-acting anti-hypertensives is strongly discouraged in the general population, there is a clinical need for immediate action in people with SCI due to the mechanisms of hypertensive crisis and a result of the emergent risk of intracranial bleed, myocardial infarction or death (Ho & Krassioukov 2010; Yoo et al. 2010).

Hospital admission is recommended if the patient is responding poorly to treatment, the cause of the AD episode remains unknown, or if your patient is pregnant. Transfer to an intensive care unit should be considered if control of the autonomic dysreflexia and its associated hypertensive crisis has not been achieved within 30 minutes.

Avoid nitrates if your patient also uses Pde5i (e.g., Viagra).

- Ask your patient and/or caregiver about their history with AD. Chances are they will be knowledgeable about how often it happens and what usually triggers an episode.

- Knowing your patient’s level of injury, age, duration of injury, usual blood pressure (BP), and usual body temperature will help in identifying Autonomic Dysreflexia. Document these baseline values and update as necessary (at least annually).

Baseline BP will generally be lower for people with SCI (100/60 mmHg +/- 20). It is important to establish your patient’s standing, sitting, and lying (supine) BP to establish their baseline and to properly monitor fluctuations.

You can simulate conditions in your office to test autonomic function, for example, with room temperature increases or instructing your patient to delay voiding their bladder, though such tests should be performed with caution. It is less likely that you will have to screen for AD as your patient will either present with or report symptoms/AD episodes.

Body temperature is easy to measure and classify, even in the early stages post-injury, and therefore, tracking any thermodysregulation may be a useful means of early assessment of autonomic function.

If you need to refer your patient with SCI and AD, it is likely because:

- an acute episode of AD is not under control so they need to go to the Emergency Room before the AD becomes (more) life-threatening, or

- acute (but controllable) AD episodes happen multiple times a day, so a visit to your local/consulting physiatrist for further examination is advised.

Other Instances where referral for AD may be necessary:

- Pregnancy – Pregnant women with SCI are at high risk of developing uncontrolled AD during the course of their pregnancies but it is especially important to recognize and prevent AD during labor and delivery.

- Surgery – AD is a common complication during general surgery in up to 90% of people with SCI undergoing surgery with topical anesthesia or no anesthesia developed AD. Patients at risk for AD can be protected by either general or spinal anesthesia.

Access to specialists (e.g., physiatry) may be limited, particularly if you do not live in or near a major city.

Advanced screening like cystoscopy as well as making recommendations re: a patient’s bladder routine may best be handled by a urologist or physiatrist with more experience in SCI.

If you or your patients with SCI are not already connected, please try to gain access to a physiatrist near you. Refer to the list of SCI centers worldwide below:

- Australia (Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service): https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qscis

- Canada: https://praxisinstitute.org/research-care/key-initiatives/national-sci-registry/registry-sites

- Europe (enrolled in European Multicenter Spinal Cord Injury Study): https://www.emsci.org/index.php/members

- UK: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/BSF_List-of-Neurocentres-in-the-UK.pdf

- USA: https://www.spinalcord.com/spinal-cord-injury-hospitals-rehabilitation-directory

(Please email SCIRE Professional if we do not have a list for your country)

Allen KJ & Leslie SJ. Autonomic Dysreflexia. StatPearls – PubMed. Accessed September 5, 2023.

Bauman CA, Milligan JD, Lee FJ, Riva JJ. Autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord injury patients: an overview. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(4):247-250. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23204565. Accessed April 28, 2020.

Teasell RW, Arnold JM, Krassioukov A, Delaney GA. Cardiovascular Consequences of Loss of Supraspinal Control of the Sympathetic Nervous System Following Spinal Cord Injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:506-516.

Stephenson RO, Klein MJ. Autonomic Dysreflexia in Spinal Cord Injury: Overview, Pathophysiology, Causes of Autonomic Dysreflexia. Medscape.com. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/322809-overview#a13. Published 2017. Accessed March 23, 2023.

Actionable Nuggets 4. Autonomic Dysreflexia (4th ed). Accessed on March 23, 2023.

Cragg J, & Krassioukov A. (2012). Autonomic dysreflexia. Journal of Canadian Medical Association (CMAJ), 8(2), 16–19. http://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110859

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Acute management of autonomic dysreflexia: individuals with spinal cord injury presenting to health-care facilities. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25 Suppl 1.

Krassioukov AV, Claydon V. The clinical problems in cardiovascular control following spinal cord injury: an overview. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:223-229.

Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV. Contemporary cardiovascular concerns after spinal cord injury: Mechanisms, maladaptations, and management. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1927-1942.

Koyuncu E, Ersoz M. Monitoring development of autonomic dysreflexia during urodynamic investigation in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40:170-174.

Krassioukov A, Warburton DE, Teasell R, Eng JJ. A systematic review of the management of autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:682-695.

Mathias CJ, Frankel HL. The cardiovascular system in tetraplegia and paraplegia. In: Frankel HL, ed. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 17th ed. Elsevier Science Publishers; 1992;435-456.

Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Krassioukov A, Laurberg S, Frandsen E, Krogh K. Autonomic dysreflexia during bowel evacuation procedures and bladder filling in subjects with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:494-498.

Liu N, Fougere R, Zhou MW, Nigro MK, Krassioukov AV. Autonomic dysreflexia severity during urodynamics and cystoscopy in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:863-867.

Krassioukov A, Biering-Sorensen CF, Donovan W et al. International Standards to document remaining Autonomic Function after Spinal Cord Injury (ISAFSCI), First Edition 2012. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2012;18:282-296.

Kirshblum SC, House JG, O’Connor KC. Silent autonomic dysreflexia during a routine bowel program in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury: A preliminary study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1774-1776.

Ekland MB, Krassioukov AV, McBride KE, Elliott SL. Incidence of autonomic dysreflexia and silent autonomic dysreflexia in men with spinal cord injury undergoing sperm retrieval: Implications for clinical practice. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:

33-39.

Wan D, Krassioukov AV. Life-threatening outcomes associated with autonomic dysreflexia: A clinical review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37:2-10.

Acute management of autonomic dysreflexia: Adults with spinal cord injury presenting to health-care facilities. Clinical practice guidelines. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;20:284-308.

Ho CP, Krassioukov AV. Autonomic dysreflexia and myocardial ischemia. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 714-715.

Biering-Sørensen F, Biering-Sørensen T, Liu N, Malmqvist L, Wecht JM, & Krassioukov A. Alterations in cardiac autonomic control in spinal cord injury. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2017; 209, 4-18. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2017.02.004

Dance DL, Chopra A, Campbell K, Ditor DS, Hassouna M, & Craven BC. Exploring daily blood pressure fluctuations and cardiovascular risk among individuals with motor complete spinal cord injury: A pilot study. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2017;40(4), 405-414. doi:10.1080/10790268.2016.1236161

Lee ES, & Joo MC. Prevalence of autonomic dysreflexia in patients with spinal cord injury above T6. BioMed Research International, 2017; 2027594-6. doi:10.1155/2017/2027594

For Clinical Practice Guideline recommendations based on your patient’s level of injury and specific complaint, click here for the CAN-SCIP Coach App.

For more information see our Autonomic Dysreflexia Module.

Disclaimer

All content and information on this website is for informational and educational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and does not establish any kind of patient-client relationship by your use of this website. The information here has been curated by experts in spinal cord injury treatment but it is not a substitute for actual medical consultation. Always see a medical professional directly for specific treatment for your particular needs including any professional, health-related, legal, medical, or financial decisions.