Primary Care and Bowel Management

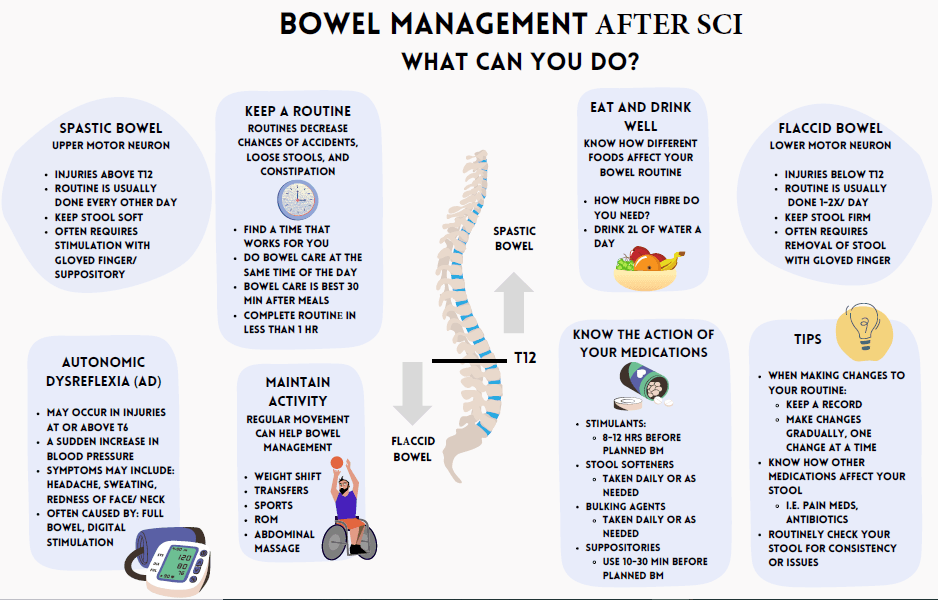

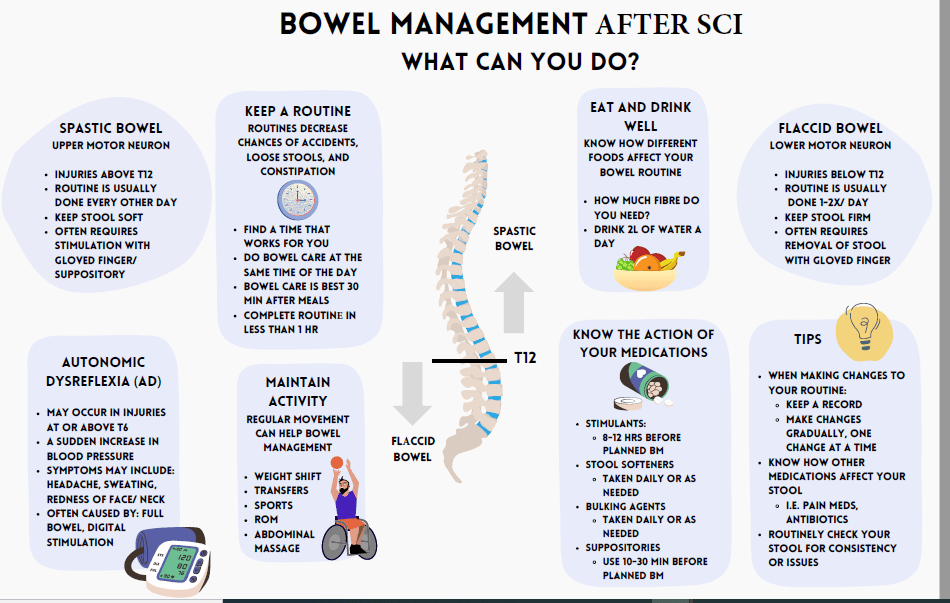

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) affects 30-95% of people with SCI, and is consistently rated as one of the most significant factors in reduced quality of life for people with SCI. Spinal cord injury (SCI) results in gastrointestinal (GI) tract dysfunctions largely due to limited or absent sensation, and the loss of reflexes and voluntary control.

Common bowel problems for people with SCI include:

- Bowel emptying that takes too long (sometimes several hours) can also interfere with life activities and increase the risk for skin breakdown (i.e., too long sitting on a toilet seat).

- Bowel incontinence or constipation (or fear of incontinence, and associated anxiety) can affect someone with SCI’s mood, and prevent them from going out, working, attending school, or having a social life.

People with SCI need to establish a regular bowel schedule and routine for health and for social continence.

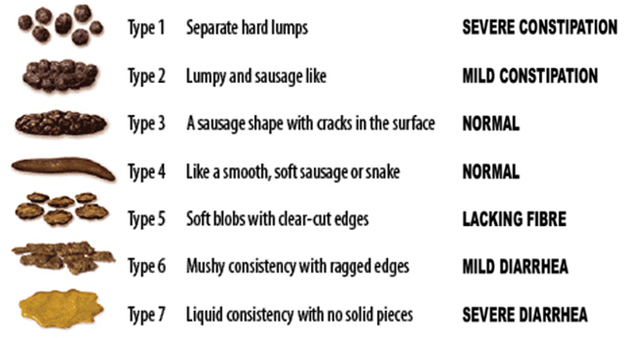

Ask your patient about their bowel movements at every appointment including how often they have a bowel movement (BM), the shape and consistency of their stool, and any episodes of constipation or incontinence.

The ideal shape and consistency of stool is a 4 on the Bristol Stool Scale (see image).

Treatment of NBD is generally multimodal and includes attention to diet and hydration, pharmacologic agents, and mechanical methods (i.e., digital rectal stimulation or abdominal massage). If no ‘conservative’ methods of bowel management are effective, some people with SCI are referred to a physiatrist for additional assistance or a gastroenterologist for possible surgery (e.g., stoma, ostomy).

A step-wise approach to SCI bowel management in primary care includes the following:

- First-line treatments: may include diet and fluid management, scheduling BMs for 20-30 minutes after eating to capitalize on the gastrocolic reflex, suppositories, irrigation, and manual assistance (i.e., digital rectal stimulation and/or abdominal massage).

- Dietary fiber should be adjusted slowly and carefully as NBD symptoms can be increased in some people with SCI when they increase their fiber intake.

- Fluid intake must be considered at the same time – i.e., the manner and frequency of bladder emptying, since neurogenic bowel and bladder often co-occur. Keeping a record of dietary intake (diet and fluid) and output (urine and stool) may be useful for patient monitoring.

- Second-line treatments: may include over-the-counter laxatives, osmotic agents, and stool-softeners, or prescription medications (prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide).

- If first- and second-line treatments fail, refer your patient to a physiatrist with more SCI experience.

- Surgical intervention may also be indicated, such as colostomy, and/or anterograde catheterization.

- Note: Your patient may ask about Epidural Stimulation for bowel and mobility improvements (i.e., an implanted stimulator in the epidural region). Preliminary results show promise, but at time of writing this is still an experimental, surgical procedure that is not yet approved in North America.

Bowel problems in people with SCI are common. You should ask your patient about their bowel routine at every Primary Care appointment. You should also have a basic understanding of common problems, solutions, and when to refer.

It would be appropriate for a family doctor to do the following:

1) Take a History – ask patients about the following:

- What is their current bowel program? What was their pre-SCI stooling history?

- Frequency of BMs, satisfaction, effects on function, and length of time to complete (ideally less than 1 hour)

- Stool consistency, including any constipation, diarrhea, or incidences of incontinence

- Abdominal distension, pain, early satiety, or nausea after eating

- Lifestyle factors – diet, fiber and fluid intake, exercise

- Comorbid conditions, and their effects on function

- Laxatives, suppositories, and medications used (including any changes in medications that may affect bowels such as antispasmodics, narcotics, anticholinergics, antibiotics)

- Excessive straining, bleeding or trauma from bowel routine, including hemorrhoids

- Autonomic dysreflexia resulting from their bowel routine and care

2) Physical examination, including abdominal and rectal

- A primary care office should include a height-adjustable table or lift to facilitate transfers to an exam table.

- Abdominal exam – Look for tenderness, any masses, crepitus or ‘joint-popping’ sounds. It can be helpful to place a pillow under the patient’s legs to help promote relaxation of the abdominal muscles and decrease spasticity.

- Rectal exam – Observe for any hemorrhoids, fissures, or other rectal masses.

- It also may be useful/simpler to assess perineal sensation; if it is present, then anorectal sensation is usually present which usually means rectal stimulants will be effective (and less painful than mechanical methods of bowel evacuation).

Screening for Colorectal Cancer:

Initiate colorectal cancer screening for patients with SCI using the same principles as those for the general population (i.e., for people between 50-74 years of age with a negative family history). A colonoscopy for someone with SCI will significantly disrupt their bowel routine so extra care and caution may be required.

Fecal occult blood testing should be conducted to screen for colon cancer bi-annually, and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 10 years). Individuals over 75 years of age should not be screened.

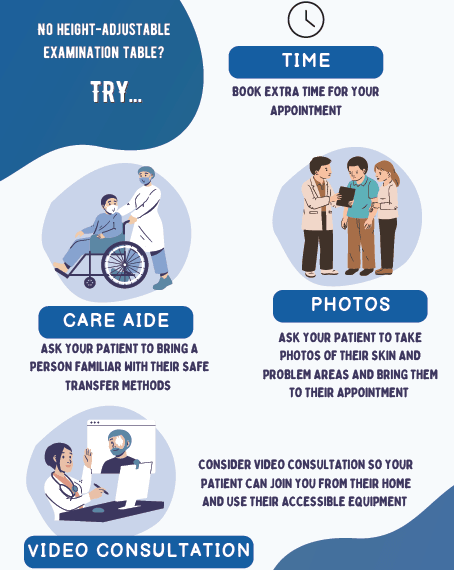

*Note: If you do not have an examination table that is height adjustable (i.e., easy for someone in a wheelchair to transfer on to), consider the following options:

- Book an extra amount of time for your patient with SCI’s appointment.

- Ask your patient to bring in a care aide or other person familiar with their safe transfer methods.

- Ask your patient to use their phone to take photos of their skin and any problems areas and bring them to the appointment.

- Consider using video consultation so your patient can join you from their home and use all of their accessible equipment for easier examination.

Refer immediately to Emergency Room if your patient’s bowel dysfunction gets rapidly worse and is accompanied by weight loss and/or blood loss.

Other Indications for Referral:

- If you patient has fecal impaction, refer to Emergency Room for acute management and then to SCI rehabilitation specialist/physiatrist and/or homecare nursing for ongoing management. Your patient may require an abdominal x-ray to help rule out obstruction.

- Frequent and/or significant autonomic dysreflexia with bowel program – refer to Emergency Room for acute management, and then to SCI rehabilitation specialist/physiatrist for ongoing management.

- If your patient’s bowel program is ineffective despite attempts to modify it, refer to SCI rehabilitation specialist/physiatrist.

Surgical management

The creation of a stoma through a colostomy or an ileostomy is generally reserved for patients who have been unsuccessful with, or who have experienced complications from, other management strategies, including Pressure Ulcers from the excess moisture from any bladder or bowel incontinence. In these cases refer to a surgeon/GI specialist.

There are about twice as many gastroenterologists as there are physiatrists, so it might be easier to get an appointment with a GI specialist doctor. However, they may not have enough experience with SCI medicine, so if your patient is dealing with NBD and your attempts to treat do not solve issues, they may need to see a physiatrist and/or a GI surgeon to consider stoma surgery.

There are about twice as many gastroenterologists as there are physiatrists, so it might be easier to get an appointment with a GI specialist doctor. However, they may not have enough experience with SCI medicine, so if your patient is dealing with NBD and your attempts to treat do not solve issues, they may need to see a physiatrist and/or a GI surgeon to consider stoma surgery.

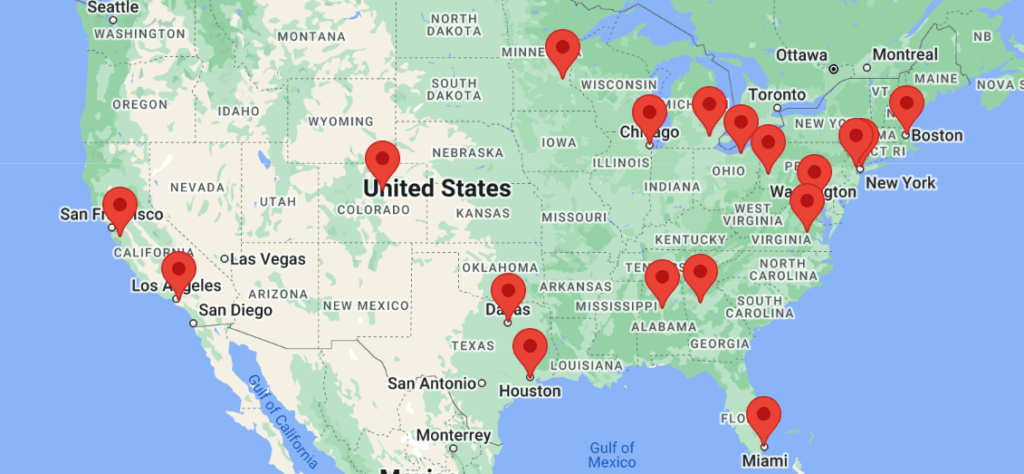

If you or your patients with SCI are not already connected, please try to gain access to a physiatrist near you. Refer to the list of SCI centers worldwide below:

- Australia (Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service): https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qscis

- Canada: https://praxisinstitute.org/research-care/key-initiatives/national-sci-registry/registry-sites

- Europe (enrolled in European Multicenter Spinal Cord Injury Study): https://www.emsci.org/index.php/members

- UK: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/BSF_List-of-Neurocentres-in-the-UK.pdf

- USA: https://www.spinalcord.com/spinal-cord-injury-hospitals-rehabilitation-directory

(Please email SCIRE Professional if we do not have a list for your country)

Pan Y, Liu B, Li R, Zhang Z, Lu L. Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury: Current Perspectives. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2014; 69, 385–388. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-014-9842-6

Adriaansen JJ, Van Asbeck FW, Van Kuppevelt D, Snoek J, & Post MW. Outcomes of neurogenic bowel management in individuals living with a spinal cord injury for at least 10 years. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015; 96, 1546-1547.

Coggrave M, Ash D, Adcock C. (2012). Guidelines for Management of Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction in Individuals with Central Neurological Conditions. Initiated by the Multidisciplinary Association of Spinal Cord, 1–60. Retrieved from http://www.mascip.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CV653N-Neurogenic-Guidelines-Se mpt-2012.pdf

Hayman AV, Guihan M, Fisher MJ, Murphy D, Anaya BC, Parachuri R. Colonoscopy is high yield in spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2003;36, 436–442. http://doi.org/10.1179/2045772313Y.0000000091

Pryor J, Fisher M, Middleton J. Management of the Neurogenic Bowel for Adults with Spinal Cord Injuries. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation; 2013.

Understanding and Managing Your Bowel Program: A guide for you after spinal cord injury. Hamilton Health Sciences; 2015.

Actionable Nuggets (4th ed. 2019). https://actionnuggets.ca/8-annual-assessment-of-neurogenic-bowel/ and https://actionnuggets.ca/9-periodic-re-evaluation-of-bowel-management-program/ and https://actionnuggets.ca/10-diet-and-fluid-management-in-neurogenic-bowel/ and https://actionnuggets.ca/11-screening-for-colorectal-cancer-in-sci-patients/

Steins SA, Bergman SB, Goetz LL. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: clinical evaluation and rehabilitative management. Archives of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation. 1997; 78, 86-102.

Kirk PM, King RB, Temple R, et al. Long-term follow up of bowel management after spinal cord injury. SCI nursing. 1997; 14, 56-63.

Levi R, Hultling C, Nash MS, Seiger A. The Stockholm Spinal Cord Injury Study: 1. Medical problems in a regional SCI population. Paraplegia. 1995;33(6):308- 315. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.70 [doi].

Lynch AC, Antony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Bowel dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(4):193-203. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101119 [doi].

Valles M, Mearin F. Pathophysiology of bowel dysfunction in patients with motor incomplete spinal cord injury: Comparison with patients with motor complete spinal cord injury. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(9):1589-1597. doi: 10.1007/ DCR.0b013e3181a873f3.

Glickman S, Kamm MA. Bowel dysfunction in spinal-cord-injury patients. Lancet. 1996;347(9016):1651- 1653. doi: S0140-6736(96)91487-7 [pii].

Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920-924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203.

Krogh K, Christensen P, Sabroe S, Laurberg S. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(10):625-631. doi: 3101887 [pii].

Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Finnerup N, Laurberg S, Krogh K. The pattern of colorectal dysfunction changes with time since spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(3):234-238. doi: 3102121 [pii].

Finnerup NB, Faaborg P, Krogh K, Jensen TS. Abdominal pain in long-term spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(3):198-203. doi: 3102097 [pii].

Clinical practice guidelines: Neurogenic bowel management in adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Medicine Consortium, 2020. Available for download (with registration) at: https://pva.org/research-resources/publications/clinical-practice-guidelines/

House JG, Stiens SA. Pharmacologically initiated defecation for persons with spinal cord injury: Effectiveness of three agents. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(10):1062-1065. doi: S0003- 9993(97)90128-3 [pii].

Branagan G, Tromans A, Finnis D. Effect of stoma formation on bowel care and quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(12):680-683. doi: 10.1038/ sj.sc.3101529 [doi].

Krassioukov A, Eng JJ, Claxton G, Sakakibara BM, Shum S. Neurogenic bowel management after spinal cord injury: A systematic review of the evidence. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(10):718-733. doi: 10.1038/ sc.2010.14 [doi].

For Clinical Practice Guideline recommendations based on your patient’s level of injury and specific complaint, click here for the CAN-SCIP Coach App.

For more information see our Bowel Dysfunction & Management Module.

Disclaimer

All content and information on this website is for informational and educational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and does not establish any kind of patient-client relationship by your use of this website. The information here has been curated by experts in spinal cord injury treatment but it is not a substitute for actual medical consultation. Always see a medical professional directly for specific treatment for your particular needs including any professional, health-related, legal, medical, or financial decisions.