Introduction

Bowel dysfunction due to spinal cord injury (SCI) results in a constellation of problems termed ‘neurogenic bowel dysfunction’ (NBD), which may include fecal incontinence, severe constipation or fecal impaction, and damage to quality of life (Emmanuel 2010; Byrne et al. 2002; Correa & Rotter 2000; Stiens et al. 1997; Glickman & Kamm 1996; Longo et al. 1995).

Even when a bowel routine to manage the problem is effective, it can be onerous and may take up to 1-2 hours per session, repeated every day or alternate days throughout post-injury life. It can interfere significantly with the person’s education, work, and social life and presents a major challenge to quality of life, independence, and community reintegration after SCI. Loss of bowel control may have greater impact than loss of ability to ambulate (Frost et al. 1993) and is a source of anxiety and distress (Ng et al. 2005; Glickman & Kamm 1996; Coggrave et al. 2009; Coggrave & Norton 2010). Ineffective bowel care results in social isolation (Byrne et al. 2002), inability to work, and admissions to acute services for treatment of fecal impaction and bowel obstruction when constipation escalates. Treatment of bowel dysfunction is often a top priority for people with SCI and their health care providers (Pazzi et al. 2021; Anderson 2004; NASCIC, 2019).

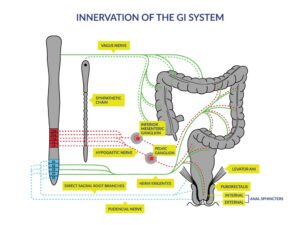

Figure 1: [1] Innervation of the gastrointestinal (GI) system. Schematic diagram of the autonomic and somatic innervations of the lower GI tract and pelvic floor. The brainstem, spinal cord and sympathetic chain are shown on the left, and the colon, rectum and pelvic floor on the right. Sympathetic innervation (dashed lines) originates from the thoracic and upper lumbar regions; parasympathetic innervation (solid lines) originates from the vagus nerve (to the upper GI and colon up to the colonic flexure) and from the sacral region of the spinal cord (to areas below the splenic flexure). Dotted lines represent the mixed nerves supplying the somatic innervation to the musculature of the external anal sphincter and the pelvic floor.

[1] Reprinted from Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 78(3), Stiens SA, Biener Bergman S, Goetz LL, Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: clinical evaluation and rehabilitative management, S86-S102, Copyright (1997), with permission from Elsevier.

Cite this Chapter: Ethans K, Smith K, Casay A, Christie C, Chu T, Querée M, Willms R, Eng J. (2024). Bowel Dysfunction and Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Townson AF, Mortenson WB, Hsieh JTC, Noonan VK, Loh E, Sproule S, Querée M (Eds). Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence. p. 1-160. Available at: https://scireproject.com/evidence/bowel-dysfunction-and-management/introduction/