Primary Care and Bladder Management

Spinal cord injury often (up to 80-85%) results in a condition called neurogenic bladder, disruption of the ability to store and void urine. Research from the USA (Model Systems Database, 2009) shows that the Top 3 leading causes of re-hospitalization after SCI were diseases of the genitourinary system (including UTIs), diseases of the respiratory system (e.g., pneumonia), and skin malfunction (e.g., pressure sores).

Bladder control for people with SCI usually requires catheterization (either intermittent, indwelling, or condom), medication (e.g., anticholinergics or botox), or in some cases, surgery; the method(s) used depend on the patient’s anatomy and remaining function. The best bladder management routine is typically determined by a physiatrist or urologist with the patient’s input. The goals of managing neurogenic bladder are continence, regular emptying, avoiding increased bladder pressure, and preventing complications.

Improper bladder management can result in significant kidney damage, kidney stones, recurrent infections, or autonomic dysreflexia. Patients with SCI are at a higher risk of UTI than people without SCI. Left untreated, UTIs can lead to sepsis, autonomic dysreflexia (life-threatening spikes in blood pressure), or other severe complications.

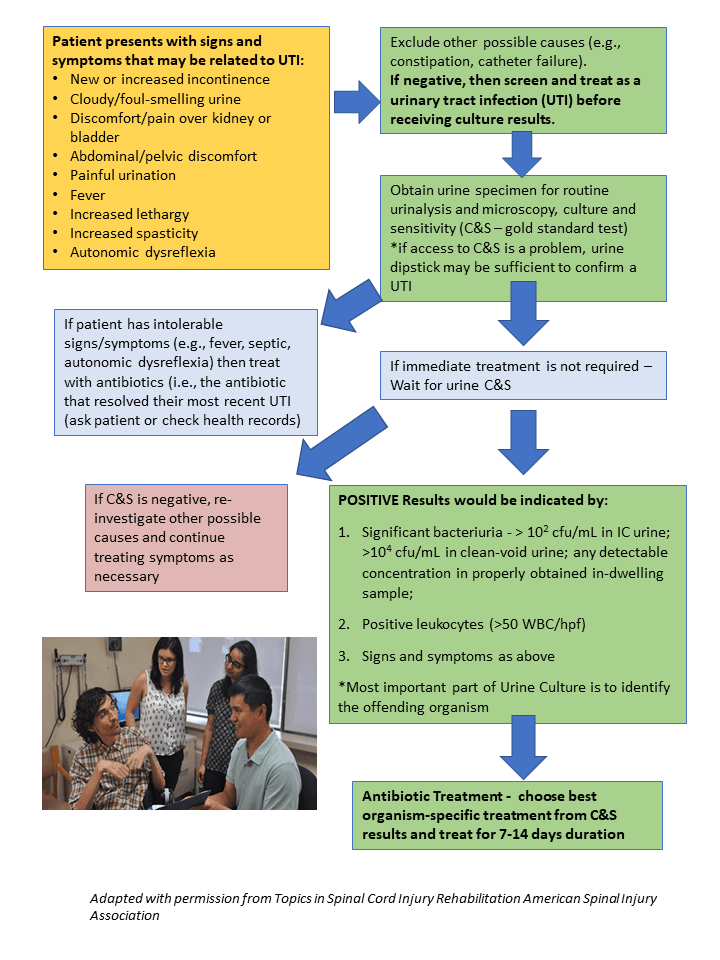

- Maintain a high level of suspicion for a UTI because some classic symptoms (painful urination, burning sensation, urgency to pee) may be absent in people with SCI, though foul-smelling urine may be detectable. Symptoms indicating UTI in people with SCI are often non-specific and may include fever/chills, nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, sweating, muscular spasms, fatigue, and autonomic dysreflexia.

- Screening (e.g., urinalysis or urine culture) should take place in presence of any of the symptoms in point 1.

- Avoid antibiotic prophylaxis and avoid antimicrobial treatment in patients without symptoms (unless discussed between physician/patient).

- Refer patient to a urologist every 1-2 years for an evaluation and an ultrasound. Urodynamic studies are recommended every 5 years or upon clinical changes. Perform yearly urologic follow-up evaluations.

- Bladder cancer risk is relatively higher in people with SCI, particularly males. Risk factors for bladder cancer with SCI include: indwelling or suprapubic catheter use, chronic UTI, bladder stones, increased urine contact time, and altered immunological function, in addition to the usual population risk factors (smoking, workplace exposure, pelvic radiation). Most patients with indwelling catheters should get a cystoscopy annually after 5-10 years of use (though if any of above risk factors are present, consider screening for bladder cancer as more urgent).

Reviewed by Dr. Rhonda Willms 02Nov2022, and Dr. Indira Lanig 17Nov2022.

Recommendations |

Details |

Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Review Patient’s Bladder Management Strategies |

|

Annually (more often if there are frequent complications |

| Kidney Function Tests |

|

Annually |

| Kidney/Upper Tract Imaging |

|

Annually or biannually |

| Urodynamics |

|

Baseline |

| Cystoscopy |

|

As needed, based on signs and symptoms |

Reviewed by Dr. Rhonda Willms Nov. 2022

Absolute indications for urology referral include:

- three or more UTIs per year,

- upper tract dysfunction or presence of chronic kidney disease,

- kidney/bladder stones,

- persistent blood in the urine,

- urethral trauma, and

- ineffective current bladder management (e.g., uncontrolled incontinence or leaking).

Reviewed by Dr. Rhonda Willms Nov. 2022. Discussion with Dr. Jamie Milligan Dec. 2022.

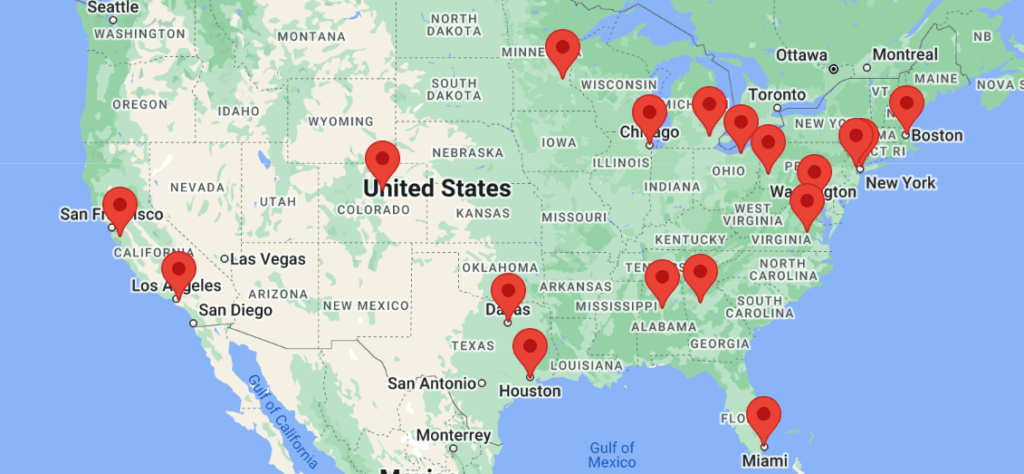

Access to specialists (urology, physiatry) may be limited, particularly if you do not live in or near a major city.

Advanced screening like cystoscopy as well as making recommendations regarding a patient’s bladder routine may best be handled by a urologist or physiatrist with more experience in SCI.

If you or your patients with SCI are not already connected, please try to gain access to a urologist or physiatrist near you. Refer to the list of SCI centers worldwide below:

- Australia (Queensland Spinal Cord Injuries Service): https://www.health.qld.gov.au/qscis

- Canada: https://praxisinstitute.org/research-care/key-initiatives/national-sci-registry/registry-sites

- Europe (enrolled in European Multicenter Spinal Cord Injury Study): https://www.emsci.org/index.php/members

- UK: https://www.brainandspine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/BSF_List-of-Neurocentres-in-the-UK.pdf

- USA: https://www.spinalcord.com/spinal-cord-injury-hospitals-rehabilitation-directory

(Please email SCIRE Professional if we do not have a list for your country)

- McKinley WO, Jackson AB, Cardenas DD, & DeVivo MJ. Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: a regional model systems analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1999; 80: 1402.

- Hsieh J, McIntyre A, Iruthayarajah J, Loh E, Ethans K, Mehta S, et al. Bladder Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, et al. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence 2014; Version 5.0: p 1-196. https://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/bladder-management/

- New South Wales Government. (2015). Adult urethral catheterization for acute care settings. Retrieved from www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/GL2015_016.pdf

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. (2006). Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America.

- McKinley WO, Jackson AB, Cardenas DD, DeVivo MJ. Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: A regional model systems analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80(11): 1402-1410. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10569434

- James Middleton, Kumaran Ramakrishnan IC. Management of the neurogenic bladder for adults with spinal cord injuries. 2013. https://www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/155179/Management-Neurogenic-Bladder.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. J Spinal Cord Med 2006; 29(5): 527-573. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17274492

- Cardenas DD, Hoffman JM, Kirshblum S, McKinley W. Etiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic spinal cord injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85(11): 1757-1763

- Amaral DM, Pereira AMVC, Rodrigues MR, Gandarez MDFL, Cunha MR, Torres MSR. Urinary tract infection in patients with spinal cord injury after urodynamics under fosfomycin prophylaxis: a retrospective analysis. Porto Biomed J (2019) 4:6(e56).

- Kim EY, Lee HJ, Kim O, Park IS, Lee BS. Should We Delay Urodynamic Study When Patients With Spinal Cord Injury Have Asymptomatic Pyuria? Ann Rehabil Med 2021; 45(3): 178-185.

- National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation: The prevention and management of urinary tract infections among people with spinal cord injuries: National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Consensus Statement. J Am Paraplegia Soc 1992; 15: 194–204.

- Przydacz M, Chlosta P, Corcos J. Recommendations for urological follow-up of patients with neurogenic bladder secondary to spinal cord injury. International urology and nephrology, 2018; 50(6): 1005-1016.

- Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Johansen TEB, Associate TCG, Çek M, Associate BKG, & Naber KG (2015). Guidelines on urological Infections by European Association of Urology. Retrieved from http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf

- Hill TTC, Baverstock R, Carlson KV, Estey EP, Gray GJ, Hill DC, … Parmar R. Best practices for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infection in the spinal cord injured population: The Alberta context. Canadian Urological Association Journal 2013; 7(3-4): 122–30. http://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.337

- Qu LG, & Lawrentschuk N. Bladder cancer surveillance in patients with spinal cord injuries. BJU International 2019; 123(3): 379-380. doi:10.1111/bju.14582

- Mishori R, Groah SL, Otubu O, Raffoul M, Stolarz K. Improving your care of patients with spinal cord injury/disease. J Fam Pract 2016 May; 65(5): 302-9.

- Actionable Nuggets (4th ed. 2019). https://actionnuggets.ca/12-monitoring-of-neurogenic-bladder/ and https://actionnuggets.ca/13-recognizing-urinary-tract-infections-in-sci/ and https://actionnuggets.ca/14-pharmacological-management-of-uti-in-sci/

Disclaimer

All content and information on this website is for informational and educational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and does not establish any kind of patient-client relationship by your use of this website. The information here has been curated by experts in spinal cord injury treatment but it is not a substitute for actual medical consultation. Always see a medical professional directly for specific treatment for your particular needs including any professional, health-related, legal, medical, or financial decisions.